Every ounce counts when designing modern machines. Lighter components help cars move faster, drones fly longer, and robots lift more with less power. In today’s market, lightweight design is not just an engineering goal — it’s a performance and sustainability requirement.

This guide explains how to design strong, lightweight parts using sheet metal fabrication. It covers materials, geometry, forming techniques, and testing methods that help engineers cut weight without losing structural integrity.

Why Lightweight Design Matters?

Reducing weight can make a big impact on cost, energy use, and performance. Even small reductions in mass often translate into better efficiency and lower total ownership cost.

Energy Efficiency and Performance

Weight affects how much energy a system needs to move or operate. In vehicles, dropping just 10% of total weight can improve fuel economy by 6–8%. For electric vehicles, every 100 kg saved can extend driving range by about 5–7%.

The same principle applies to drones, industrial robots, and aerospace systems. When parts weigh less, motors use less torque, and batteries last longer. The benefits multiply across the system — smaller parts mean smaller motors, lighter supports, and lower energy demand overall.

Cost and Sustainability Benefits

Lightweight design also supports cost control and environmental goals. Using less raw material reduces production cost and minimizes scrap. It also lowers shipping weight, cutting transportation emissions and improving sustainability compliance with standards such as ISO 14001.

Even when advanced materials like aluminum or titanium cost more per pound, they often pay off through reduced energy use, easier handling, and better long-term durability. For many U.S. manufacturers, lightweighting is a key step toward meeting both performance and eco-efficiency targets.

The Role of Sheet Metal Fabrication in Weight Reduction

Sheet metal fabrication is one of the most effective ways to create strong yet lightweight parts. It allows precise shaping, fast production, and consistent quality — all with less material use than machining or casting.

High Strength-to-Weight Ratio Advantage

Sheet metal can achieve high stiffness with minimal mass when shaped correctly. For example, a 0.8 mm aluminum panel can match the stiffness of a 1.5 mm steel plate, depending on geometry. That means a nearly 50% weight reduction without losing strength.

Engineers rely on the strength-to-weight ratio — yield strength divided by density — to select the right material. Aluminum alloys like 5052-H32 and 6061-T6 are common choices for brackets, panels, and enclosures. Thin-gauge stainless steel is used when higher surface durability or corrosion resistance is needed.

Because sheet metal builds strength through form rather than thickness, engineers can achieve performance targets while using less material.

Design Flexibility and Forming Options

Sheet metal fabrication supports multiple forming methods — bending, flanging, deep drawing, and embossing — allowing complex shapes to be created from a single flat sheet. This process builds rigidity and functionality without adding thickness.

Unlike machining, which removes material, or casting, which fixes shape early, sheet metal creates strength through geometry. Proper use of bends, ribs, and flanges distributes loads more efficiently. For instance, a simple 90° flange can raise stiffness by up to 40%, improving resistance to bending and vibration.

This flexibility lets designers combine multiple parts into one integrated form, reducing joints, welds, and fasteners — all of which contribute to unnecessary weight.

Material Selection for Lightweight Sheet Metal Parts

The right material defines how light, strong, and manufacturable a part will be. Each metal offers a different balance between strength, cost, and formability.

Common Lightweight Materials

| Material | Density (g/cm³) | Strength-to-Weight | Corrosion Resistance | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum (5052, 6061) | 2.7 | Excellent | High | Enclosures, panels, automotive frames |

| Stainless Steel (304, 316L) | 7.9 | Good | Very High | Industrial housings, brackets, cabinets |

| Titanium | 4.5 | Superior | Excellent | Aerospace, medical, high-performance parts |

| Magnesium Alloys | 1.8 | Moderate | Fair | Electronics, lightweight covers |

Aluminum is the go-to choice for most lightweight sheet metal projects. It combines low density, strong corrosion resistance, and good machinability.

Stainless steel is heavier but can be used in thinner gauges while keeping high stiffness. It’s ideal when parts face vibration, impact, or exposure to heat and chemicals.

Titanium has the best strength-to-weight ratio but higher cost and forming difficulty. It’s used mainly where every gram matters, such as aerospace structures. Magnesium alloys are the lightest option but require special handling to avoid corrosion and fire risks.

How to Balance Strength, Cost, and Machinability?

Selecting the right material means finding the best trade-off between mechanical performance and production efficiency. Aluminum often provides the best value for large-scale fabrication due to low tool wear and short cycle time. Stainless steel fits applications that need durability in harsh conditions.

When choosing a material, engineers usually compare:

- Density – weight per volume.

- Yield strength – how much load it can handle before bending.

- Formability – how easily it can be bent, drawn, or cut.

- Surface finish – how it looks and resists corrosion.

Combining materials is also a growing trend. For example, using an aluminum shell with stainless inserts in wear zones keeps parts light while extending service life.

Design Strategies to Reduce Weight Without Sacrificing Strength

Lightweight sheet metal design focuses on how shape, geometry, and load paths interact. The goal is not to remove material randomly but to use form and structure to carry force more efficiently.

Optimize Geometry and Wall Thickness

Geometry is the foundation of every strong yet lightweight part. A flat sheet flexes easily under pressure, but a bent or folded one resists deformation much better.

Adding a 90° bend or flange can increase stiffness by up to 40–50% with little extra material. The same principle applies to folds, hems, and boxed edges — these features strengthen the part without adding thickness.

Start by studying where the part carries load. Keep thicker walls only where stress is concentrated — around corners, mounting holes, or structural supports. Reduce thickness in flat, low-stress regions. For example, moving from 1.2 mm to 1.0 mm aluminum cuts material use by about 17% without major strength loss if geometry is optimized.

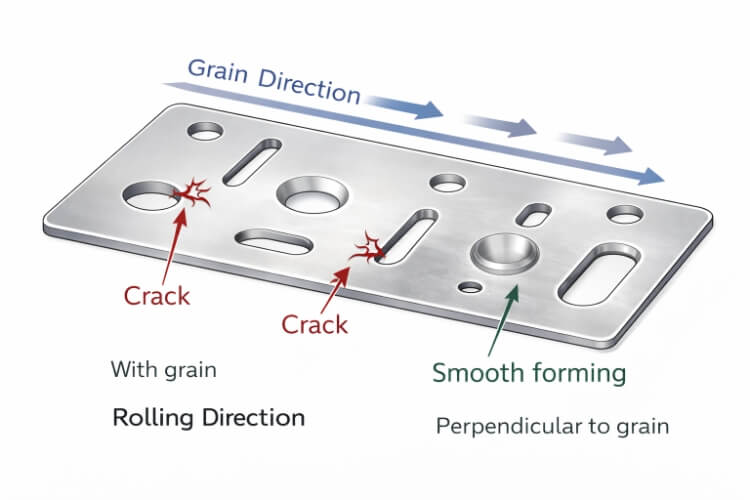

However, always consider formability. Very thin sheets can wrinkle or crack during bending. Maintain a minimum bend radius (1–1.5× thickness for aluminum, 1.5–2× for steel) to keep forming consistent and avoid tool marks.

Use Structural Reinforcements

Reinforcements help thin materials act like thicker ones. Adding ribs, beads, or return flanges distributes stress and improves rigidity in large panels or enclosures.

A V-shaped bead or a small embossed rib can increase local stiffness several times without adding measurable weight. Engineers often place these features along load paths or across flat spans to reduce deflection.

Rounded corners and soft transitions between bends also lower stress concentration. Sharp corners can act as crack starters, especially in high-load areas.

For example, a thin stainless cover panel with 1 mm ribs can resist the same pressure as a 1.5 mm flat plate, reducing mass by roughly 30%.

Introduce Cutouts and Perforations Strategically

Cutouts are an effective way to reduce unnecessary mass while adding function. They can improve airflow, allow cable routing, or simply reduce panel area.

However, hole placement requires care. Poorly located openings can weaken a bend or cause cracking during forming. Always keep at least 2–3× material thickness between a hole and any bend line.

Perforated patterns work well on covers or guards that don’t bear heavy loads. They improve cooling and reduce weight while keeping structural stability. Symmetrical hole layouts also prevent warping during press forming or laser cutting.

Simplify Assembly Through Integration

Every joint adds material, time, and cost. Integrating features directly into the sheet design can save all three.

For example, instead of welding on brackets, form them into the base sheet with flanges or tabs. A single bent component can replace several small parts and fasteners. This approach shortens assembly time, reduces welding heat, and minimizes alignment errors.

Integrated design also improves quality control. Fewer joints mean fewer weak points — and less cumulative tolerance buildup across assemblies.

Simulation and Validation in Lightweight Design

Lightweight design always needs verification. Simulation and testing confirm that thinner, optimized structures still meet strength and safety requirements.

Finite Element Analysis (FEA) for Stress Evaluation

FEA lets engineers test virtual prototypes before production. The software divides the part into small mesh elements, then calculates how each reacts under load.

By reviewing the stress map, you can spot weak zones and redesign before cutting metal. For instance, if a flat section shows high stress, adding a rib or curve can drop stress by 20–40%.

Modern FEA tools like SolidWorks Simulation, ANSYS, or Fusion 360 make it easy to evaluate stiffness, vibration, and buckling even for thin-wall parts. This reduces rework and shortens design-to-production time.

For critical components, engineers combine simulation with physical validation — ensuring digital results align with real behavior.

Prototyping and Testing

Physical testing confirms that real parts match digital predictions. It also helps uncover practical issues such as tool marks, weld distortion, or vibration noise.

Common validation steps include:

- Bend Tests – check flexibility and cracking behavior.

- Fatigue Tests – assess how the part performs under repeated cycles.

- Vibration Tests – verify stiffness and resonance performance.

Lightweight parts often fail through fatigue rather than overload. Testing under real conditions ensures that reduced-weight designs still maintain safety margins.

Rapid prototyping — such as laser-cut mockups or 3D-printed fixtures — allows engineers to test fit, stiffness, and assembly early before committing to full tooling.

Manufacturing Considerations

Designing lightweight sheet metal parts is only the first step. Making them work in real production requires understanding forming limits, joining methods, and surface finishing.

Forming Limits and Tooling Constraints

Every material bends and stretches differently. Understanding these limits helps avoid cracks, wrinkles, or distortion during forming.

For most aluminum alloys, the minimum inside bend radius should be at least 1.5× material thickness. Stainless steel usually needs 2× thickness because it is harder and less ductile. Pushing below these limits often causes surface marks or stress fractures.

Tooling setup also affects lightweight fabrication. Thin sheets can flex or shift during forming, which leads to inconsistent angles. Using precision press brakes, servo presses, or CNC bending machines ensures consistent results across multiple runs.

Complex parts may require several forming stages or progressive dies. To control cost, it’s better to simplify geometry so standard punches and dies can do most of the work. This approach keeps tooling investment low and reduces the risk of variability between batches.

In high-volume production, accurate forming also improves assembly alignment. A small 1° bend error can create visible gaps or stress points when assembling enclosures or panels. Tight control during forming ensures each lightweight part fits correctly on the line.

Joining Methods for Thin Sheet Metal

Lightweight parts use thin walls, which makes joining more delicate. Choosing the right joining technique depends on the material, part thickness, and required load strength.

Spot Welding – Works well for steel and some aluminum alloys. It’s fast and consistent but requires proper spacing between weld points to avoid panel warping. For aluminum, additional cleaning and clamping pressure improve weld quality.

Riveting and Fasteners – Mechanical joining is ideal when heat from welding might damage coatings or cause distortion. Blind rivets and self-clinching fasteners are widely used in electronics, aerospace, and enclosure assemblies. They also make repairs or disassembly easier later.

Adhesive Bonding – Provides even load distribution and prevents heat distortion. It’s useful for thin or dissimilar metals that are hard to weld. Modern industrial adhesives can achieve shear strengths above 20 MPa, similar to some weld joints. Bonded joints also improve vibration resistance.

Some engineers combine methods — such as adhesive + rivet — to balance strength and sealing performance. This hybrid approach keeps joints lightweight while improving durability under vibration and thermal cycling.

Surface Finishing for Durability and Appearance

Lightweight metals often need surface protection to prevent corrosion and wear. Since thin materials have less “sacrificial” layer, finishing becomes critical for long-term performance.

Anodizing is common for aluminum. It adds a hard oxide coating that resists scratches and corrosion. The oxide layer is part of the metal, so it doesn’t peel or chip like paint. It’s ideal for enclosures, panels, and frames exposed to outdoor environments.

Powder Coating gives both protection and color. It creates a uniform, durable surface that resists chipping better than liquid paint. It’s often used for industrial housings or cabinet panels.

Electroplating improves conductivity and corrosion resistance. Nickel or zinc coatings protect steel surfaces and enhance appearance.

For stainless steel, brushed or mirror-polished finishes work well without additional coating. They reduce fingerprints and oxidation, especially for consumer-facing products.

Environmental regulations also matter. Many manufacturers now use RoHS-compliant and eco-friendly coatings to meet sustainability goals without compromising performance.

Quality and Tolerance Management

Lightweight designs are more sensitive to small dimensional changes. Thinner sheets can deform easily during cutting or welding. Setting realistic tolerance zones and working closely with fabrication engineers helps maintain consistency.

Using Design for Manufacturability (DFM) principles ensures that each bend, hole, and weld fits within the equipment’s capability. Early collaboration between designers and the shop floor often prevents costly rework and scrap later.

Laser cutting, nesting optimization, and CNC-controlled bending all support high accuracy and minimize waste. These tools make lightweight production efficient while maintaining repeatable quality.

Conclusion

Lightweight sheet metal design is not just about cutting thickness. It’s about understanding how shape, structure, and process work together to create strength with less material.

Modern fabrication tools — from laser cutting to CNC bending and FEA simulation — make it easier to design parts that meet both strength and cost goals. By using geometry wisely, reinforcing critical areas, and validating through testing, engineers can achieve durable, lightweight solutions that perform reliably in real conditions.

Ready to design lighter, stronger sheet metal parts? Our engineering team can help you optimize geometry, select materials, and validate performance through simulation and prototyping. Send us your drawings or models for a free DFM review and weight-reduction consultation.

FAQs

What materials work best for lightweight sheet metal parts?

Aluminum is the most common choice because of its high strength-to-weight ratio and corrosion resistance. Thin-gauge stainless steel works well for parts that need higher durability.

How can I make a part lighter without losing strength?

Add ribs, flanges, or folds to strengthen flat surfaces. Use thicker metal only in high-stress areas. Geometry often improves stiffness more effectively than thickness.

How does simulation help in lightweight design?

Finite Element Analysis (FEA) predicts stress and deformation before fabrication. It helps engineers adjust geometry early, cutting down prototype cycles and material waste.

Why is surface finishing important for thin materials?

Thin materials are more sensitive to corrosion and wear. Finishes like anodizing, powder coating, or plating extend product life and improve aesthetics.

Hey, I'm Kevin Lee

For the past 10 years, I’ve been immersed in various forms of sheet metal fabrication, sharing cool insights here from my experiences across diverse workshops.

Get in touch

Kevin Lee

I have over ten years of professional experience in sheet metal fabrication, specializing in laser cutting, bending, welding, and surface treatment techniques. As the Technical Director at Shengen, I am committed to solving complex manufacturing challenges and driving innovation and quality in each project.